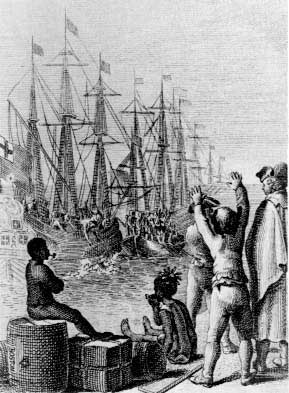

Die Eiwohner von Boston wersen den englisch-ostindischen Thee ins Meer

Boston Tea Party

Disney's Tea Party: Johnny Tremain

and the Sons of Liberty (1958)

Disney’s 1958 movie, Johnny Tremain and the Sons of Liberty,

tells the story of an "ordinary" boy’s experience of

the Boston Tea Party. Johnny Tremain is an orphan, and a young silversmith’s

apprentice in Boston. In the opening scene of the movie, he and his

master undertake a difficult commission: a silver teapot for Jonathan

Lyte, a Boston aristocrat (Scene 1). In the process, Johnny seeks

out the help of master silversmith, Paul Revere, thereby encountering

the radical politics of the Sons of Liberty and their protests against

the tax on tea (Scene 2). After being dismissed from his apprenticeship

because of an injury to his hand, Johnny comes into conflict with

Boston elites when he attempts to prove that he is in fact Jonathan

Lyte’s long-lost nephew. Falsely accused of stealing a silver

pitcher, he is ably defended in Court by a member of the Sons of Liberty.

Needless to say, Johnny joins the Sons of Liberty shortly thereafter.

On the night of the Tea Party, it is Johnny who, at Sam Adams’s

command, gives the whistle blow from the Old South Church signaling

to the Sons of Liberty to begin the destruction of the Tea (Scene

3). After his participation in the Tea Party, Johnny goes on to fight

at Lexington & Concord. As the movie ends, he looks forward to

continuing the fight for liberty.

As you watch these scenes from Johnny Tremain, ask yourself how this portrayal of an "ordinary" person’s involvement in the Boston Tea Party compares to that of George Hewes’s memoir, or Alfred Young’s interpretation of that memoir. Consider, for example, the depiction of the relationships between Johnny and his master, or the loyalist aristocrat, or famous revolutionary leaders such as Revere and Adams. Also notice the ways in which gender, race, class and status relations are demarcated or transgressed in the film. How has the popular memory of the Boston Tea Party evolved from the 1770s to the 1830s to the 1950s and beyond?